(Author’s Note: This is almost the end of what I call “The Prologue” as this entry will bring us one post closer to the present and what I’ll call the “Treatment” entries. Everything after will be as close to the present as I can manage.)

You’re Young Enough.

Trying to go to sleep the first evening back from the hospital was a chore. I’m not someone that can easily fall asleep on my back, and rarely on my actual side. Typically I sleep as if I’m in the prone unsupported position with a pillow under my arm to combat a pre-existing nerve condition I’ve been battling over a year called ulnar tunnel syndrome. On my stomach was a non-starter with the fresh tube hanging out of me, and the pillow was going to dig right into it. Fuck! On top of all the other jarring changes I just underwent, now I had to change how I slept, too.

My exhaustion overcame me and I managed to fall asleep listed to my side like I was back in the hospital bed. My abs were still weak and would remind me of the new hole in them whenever I did anything resembling sudden movement, so I wasn’t terribly worried about rolling around. It wasn’t a very restful sleep; there was a lot of tossing and turning, but eventually this wreck of the Cancer Fitzgerald sunk into the bed long enough to have sleep that was unbroken by vitals checks and vomiting.

There was no rest for me, however, as I had referrals to go to the next day. First up was with the ENT Oncologist, a civilian specialist at a nearby civilian hospital. Despite the recommended treatment from the tumor board at the Army hospital, they hinged it on, “but still go see Dr. Shannon, we want to know what he thinks.” So here I was, crouched over my Army hospital-grade walker in the frozen parking garage of the hospital with my mom, inching my way toward a second opinion.

Dr. Shannon’s office was unremarkable… with the notable exception of my presence in the waiting room. Every other patient in the room was old enough to have one foot in the grave, and all of them stared at me at one point. Me in my walker just waiting to be called back; I could feel their bewilderment. This was as close to feeling like Rosa Parks in the wrong bus section as a young white guy can get.

After being called back I scooched my way into the exam room and sat in the upright padded exam chair for what I knew was going to likely happen here: another scoping.

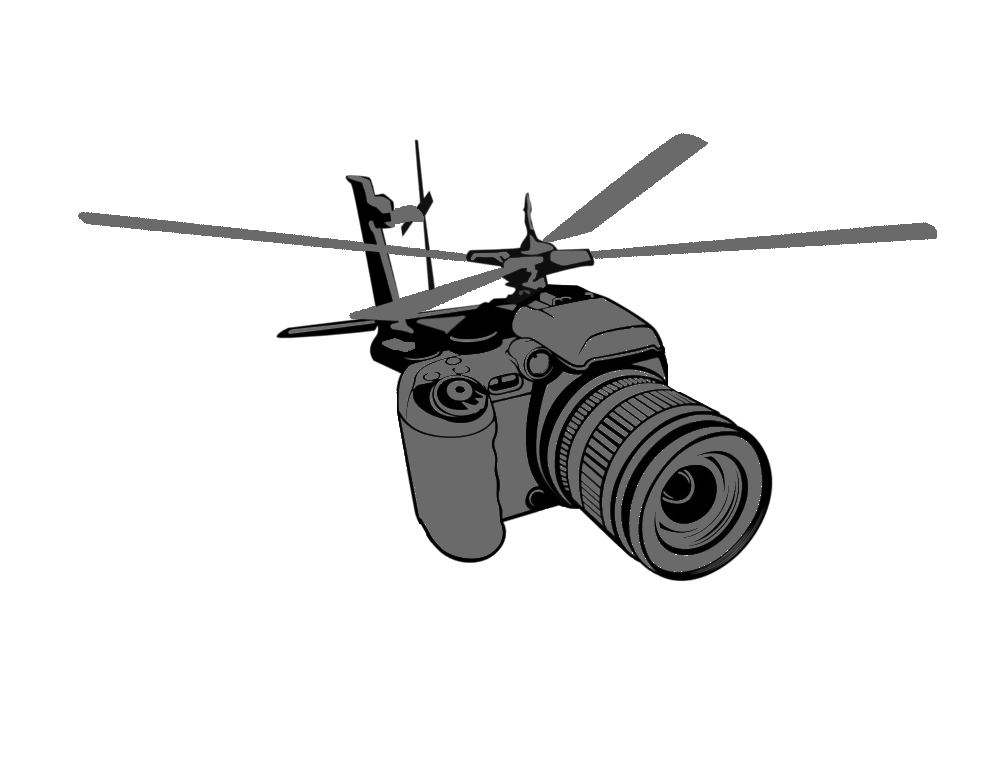

When you get scoped, it means they are shoving a camera into one of your orifices to do a visual inspection. In my case, this involved taking a camera on a flexible metal hose, a little smaller in diameter than a soda straw, and sliding it up my nose and into the back of my throat to take a look at the tumor (see this post for an example of what a scope sees).

I was correct. Dr. Shannon scoped me, did an exam on my neck, and asked me some questions. He’d already seen all of my imagery from the Army hospital, and had spoken to Dr. Sierra about my case. What he thought about this was not only going to be factored into my care team’s decision making process, but my own, as he was a regarded specialist by them.

He recommended against surgery. Whew? I guess this is the part where I started to repair my battered trust in the medical establishment after the last 48 hours: This guy had nothing to gain by recommending I not do the very thing he and his hospital profited from. My ENTs were not certified to do this surgery, so it would have fallen to him, and he knew that. Yet, he agreed with their treatment plan to the letter, and explained why. In this world, professional ethics are under siege across society, and this man held the line. Bravo, Dr. Shannon, bravo. (I suppose it also didn’t hurt that one of my colleagues’ wife is his colleague and name-dropped me prior to the appointment. Hooray for serendipity.)

Next up was a ride to the Army hospital for my first meeting with the Medical Oncologist (Med Onc) chief, Dr. Ferrell. Dr. Ferrell was very highly regarded by everyone on the Army medical staff so far that mentioned his name. A “made man” of sorts, because not only had he been doing his job in the hospital for a long time as an oncologist, but he was also a full bird Colonel in the Army Reserve in the same capacity.

I once again sat in waiting room with my mother, where everyone else was 35+ years my senior and clearly had spent a lifetime around loud noises, as the two men talking to each other next to us demonstrated with their loud voices and the constant use of “WHAT?” I was again viewed with a curious eye as I plopped into the seat from my walker.

The Army is, culturally, a strange place. Army hospitals are not exempt from this. We have expensive, complicated, digital systems that store all of our information from clothing issue records, to administrative files, promotions, and yes, medical data. Despite this, either out of habit or convenience, many of these offices require paper forms to be filled out that force you to recall all of the information that could be pulled up in a few mouse clicks with the proper permissions. I was just about at the end of my rope with this.

I took one look at the very poorly photocopied forms and started to get into a bad mood, either from stress, frustration, sleep deprivation, pain, or some combination. I filled out the administrative data and wrote on them, “All of this information is visible in my digital record” and turned the forms in. One of two things then happened: either the clerk at the desk stuck the forms into some folder that will never see the light of day, or less likely, they understood they were just going through the motions with this practice and my small act of medical disobedience was understandable.

Dr. Ferrell came to greet us and walked us back to his office. He had the air of someone who was quietly, calmly, confident, but was ready to be proven wrong- my kind of guy. We talked through his role in my treatment: he was to oversee the administration of my chemotherapy treatment.

I absolutely hammered him with questions. This was the guy I really wanted to talk to since this whole thing kicked off and he was able to answer all of my questions, or at least satisfy my curiosity. He went over the treatment plan and told me I was going to get the most aggressive treatment for my cancer, because, “you’re young enough to handle it, and it’s unlikely we will damage your kidneys.”

I am so tired of hearing about how young I am.

============

America, Tkachuk Yeah!

Cisplatin was the name of the drug I was prescribed in my treatment plan for chemotherapy, and I was prescribed the maximum dosage to work in concert with my radiation. Potential side effects: hearing loss, kidney damage, immune system degradation, hair loss, and sterilization. Another fun grab bag of side effects to mirror the hellscape that radiation therapy also presented.

It was at this time that the possibility began to creep into my mind that this cancer wasn’t just trying to kill me, it was trying to kill my Army career. Some of the side effects from the treatment of this condition are career-enders, in either a medical “chapter” (discharge) or medical retirement, and that wasn’t an outcome I’d considered until I had some time to piece that together in my mind.

Take one brick of stress off, replace it with ten more.

The next day, however, radiology oncology (Rad Onc) techs started to second guess some of the worst of the aforementioned side effects based on their experience when mapping me. They told me that a number of their head and neck patients kept their hair, and told me not to shave mine down preemptively like I’d planned, because it would screw up the mapping process later.

Mapping involved a few interesting experiences. I showed up, again with my mother who by this time was amassing a phonebook-sized folder of medical paperwork to tote with me to each appointment, and was called back by the two Rad Onc techs that would be handling my treatments. The only previous instructions I’d received were, “be clean shaven for mapping, and each of your treatments” and while I mourned the loss of my mustache, it was for a greater good.

I had to make a mouthpiece first. Anyone who has made a mouthpiece for contact-sports knows that this involves heating up a piece of solid mouthpiece-shaped rubber and then softly biting into it until it cools around teeth to ensure proper fit when you need to wear it. The second part of mapping was having a giant head and shoulder soft cast made from a pliable mesh material that also was heated up… to make a mouthpiece-type impression of my upper body. This process was very thorough, as this mask had to hold my head perfectly still each time at each treatment. Any margins or gaps would mean having to have the mask re-made and I’d have to be remapped. The mouthpiece I’d just made was clipped into the mask perfectly, and they tested the fitment of the whole system with a fancy machine that was similar to a CT in many ways. Last I was punched with a tiny tattoo of infrared ink on my chest for the laser to read each time, and that was it. Rounds complete: I was a ‘go’ at this station.

One thing I’m really glad the techs did prior to leaving was offer me a tour of the radiation therapy suite. I took them up on this and was guided into a room that looked like some sort of chamber from the Death Star. I suppose this is oddly appropriate since the cancer will likely view this the same way. There’s a flat table that a machine revolves around and shoots radiation in photon beams into the tumor. The whole process is supposed to last only a few minutes; you spend more time in prep and tear-down than you do actually getting zapped.

The next day I went on a date with Addison to our local junior league team and she’d gotten us seats just two rows up from the penalty boxes, which was a fun experience given how much fighting goes on at the lower levels of hockey. As previously mentioned, Addison is Canadian by birth and had a rooting interest in the “4 Nations Faceoff” tournament as Canada and the U.S. were playing while we were at this game.

I’d fully planned on leaving it alone, figuring Canada’s absolute star-studded roster would roll through every other team, so no shit talking would’ve bore any fruit, but once Canada went up 1-0 she couldn’t help but start in on how, “The U.S. needs to be humbled.” This coming from a citizen of a country that wins 75%+ of international hockey tournaments and still provides the plurality of NHL players was rich, so when the U.S. took the lead off of Dylan Larkin’s unassisted goal and then hit the empty-netter at the end to win, I let her have it. It wasn’t until after the game ended that the highlights rolled into my phone of USA’s Tkachuk brothers being two thirds of the fights in the first nine seconds of the game. USA, USA, USA! I let her have it the rest of the evening, and the following day, as Instagram put forth some wonderful reels equating them to the Smash Brothers from The Mighty Ducks franchise.

It was a critical morale boost as I began to truly contemplate what future me would look like.

The views and opinions presented herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Army.

You must be logged in to post a comment.